Dalston Works, completed in Summer 2017, is the world’s largest timber building. It was designed by sustainability specialists Waugh Thistleton Architects. I spoke with Dave Lomax, Senior Associate at the practice.

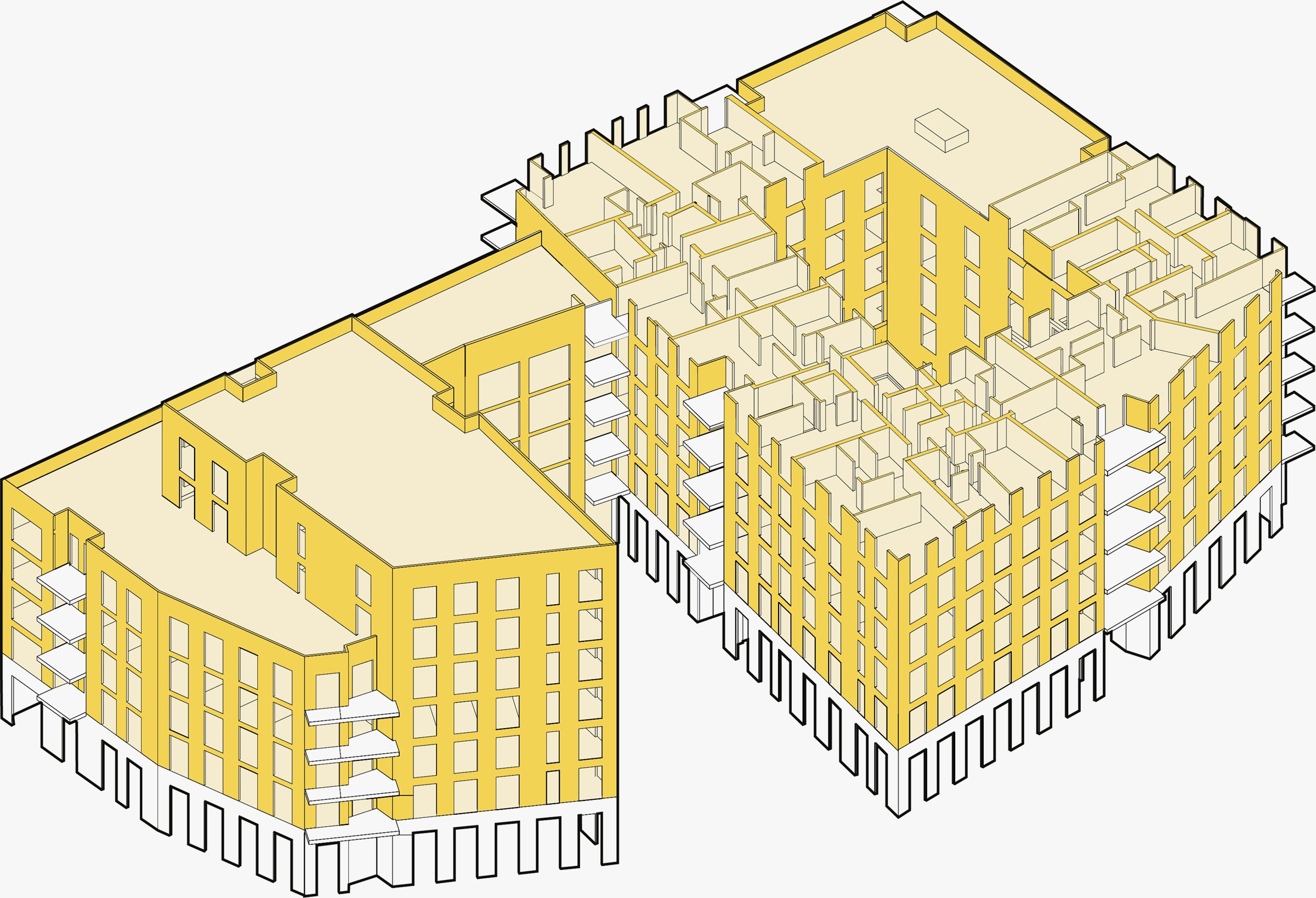

Built for London Developer Regal Homes, Dalston Works is a ten-storey complex housing 121 flats, as well as over 3,460 m2 of commercial space. Whilst the third tallest timber building in the world as of October 2017, at 33m, it is the largest in terms of the volume of timber used.

Large scale timber construction comes in a variety of forms. The world’s tallest timber building, 18-storey Tallwood Residence in Vancouver, is 53 metres tall and has a hybrid structure of laminated wooden beams (Glulam) and concrete lift cores. Dalston Works, meanwhile, consists of cross laminated timber (CLT) panels, from the first floor up.

Cross laminated timber is an engineered product, produced in large sheets. These are typically up to 13.5 meters long and 3.5 meters wide. In the factory, kiln-dried timber is glued in layers at right angles and pressed, forming high strength panels. Before they are transported to site, window and door openings are cut. The panels form the walls and ceilings and can be quickly assembled.

A High Performance Structure

The 3,853 cubic metres of CLT in the building act as carbon storage, with 2,600 tonnes of CO2 locked into the fabric. Meanwhile, it has less than half the embodied carbon – atmospheric CO2 release – of a conventional steel and concrete building.

The precision-cut panels lend themselves to airtightness, allowing Dalston Works also to perform well in terms of energy-in-use. The building achieved CSH 4, and a BREEAM silver rating for the commercial areas.

Crucially, using CLT made a success of a site that presented major challenges. The Channel Tunnel rail link runs directly underneath; in the future so too will the second phase of Crossrail. This placed tight constraints on the ground works, and the weight of the overall structure. Due to the use of CLT, Dalston Works is a fifth the weight of a conventional building the same size. This meant smaller foundations were needed, and it was possible to include 14 more residential units than otherwise.

This is not the first CLT high-rise by Waugh Thistleton; they designed 9-storey Murray Grove, a residential tower in Hackney, completed in 2009. Since then they have refined the technique; at Dalston Works they tapered the thickness of the panels, getting thinner higher up. This reduced both weight and materials used.

Importantly, CLT also performs well in terms of fire safety – a subject particularly in the public mind since the 2017 Grenfell Tower tragedy. Unlike steel, CLT remains structurally stable when subjected to high temperatures. Additionally, the panels can be produced with fire resistances of up to 90 minutes. Their fire resistance arises as the surface exposed to fire turns to char, insulating the core of the panel.

Developer perspective

Sustainability cannot realistically be the only deciding factor when a developer chooses the construction technique for a project; it has to make commercial sense. I spoke with Lucy Whitehead, marketing director at Regal Homes, to see why they chose CLT for Dalston Works.

We jointly made the decision with Waugh Thistleton Architects, based on the design, the location, the type of accommodation and access routes. The speed of construction, and the resulting speed of delivering the homes, were benefits to using CLT and off-site manufacturing. We were also able to reduce construction traffic through the use of this method.

Asked if they see CLT taking over from conventional methods, Lucy notes that construction methods need to be chosen on a development by development basis, and sometimes CLT is unsuitable. It is worth noting that CLT does not lend itself to much floor plan flexibility, but other wooden structures – Glulam and LVL for example – do have this advantage.

Signs of change in the UK construction industry

Demonstrating its impact, Dalston Works was used as a case study by the London Assembly Planning Committee when launching their manifesto for off-site construction. Encouragingly, the committee suggests CLT and pre-fabricated construction could help to improve London’s housing shortage.

Nicky Gavron, Chair of the London Assembly Planning Committee, visits Waugh Thistleton’s Pitfield Street development in Hackney

Meanwhile, there are further signs that the use of this kind of construction technology is expanding. Berkeley Homes have built a factory for modular offsite construction near the Dartford crossing; financial services company Legal & General are also persevering in developing the system.

Nicely summarising the success of the build, Regal Homes note that the borough Council was an enthusiastic supporter of the scheme. The following is from Hackney Councillor Stops: “this building shows great design and construction… The building’s environmental credentials are second to none. Constructed with mass timber, it’s the most significant development of its kind in the world, in Dalston!”

Architect: Waugh Thistleton Architects

Developer: Regal Homes

CLT engineer: Ramboll

Timber erector: B&K Structures

Awards:

AJ Sustainability 2017 (Highly commended)

Structural Timber 2017 Solid Wood/Housing/Overall (Winner)

NLA 2017 Housing (Commended)

NLA Ashden 2017 (Highly commended)

Offsite 2017 (Highly commended)

RICS Awards 2018 (Shortlisted)

Construction News 2018 (Shortlisted)