Sustainable settlements like Hockerton Housing Project are a model of a potential future. There are lifestyle changes and time commitments for the inhabitants, and I was keen to see how this worked in practice.

There are several sustainable settlements around the UK and Republic of Ireland – for example, Lammas Ecovillage in Pembrokeshire, and Cloughjordan in Co. Tipperary. Hockerton Housing Project in rural Nottinghamshire was founded in the 1990s. The 15-acre settlement has grown from 5 earth-sheltered homes.

Beginnings

The site was obtained in the early 90s. In August 1996 the group made post-war UK planning history, achieving special permission for a development on agricultural land. Hockerton was to be a ‘whole living project… the occupants will work towards a system of self-sufficiency’.

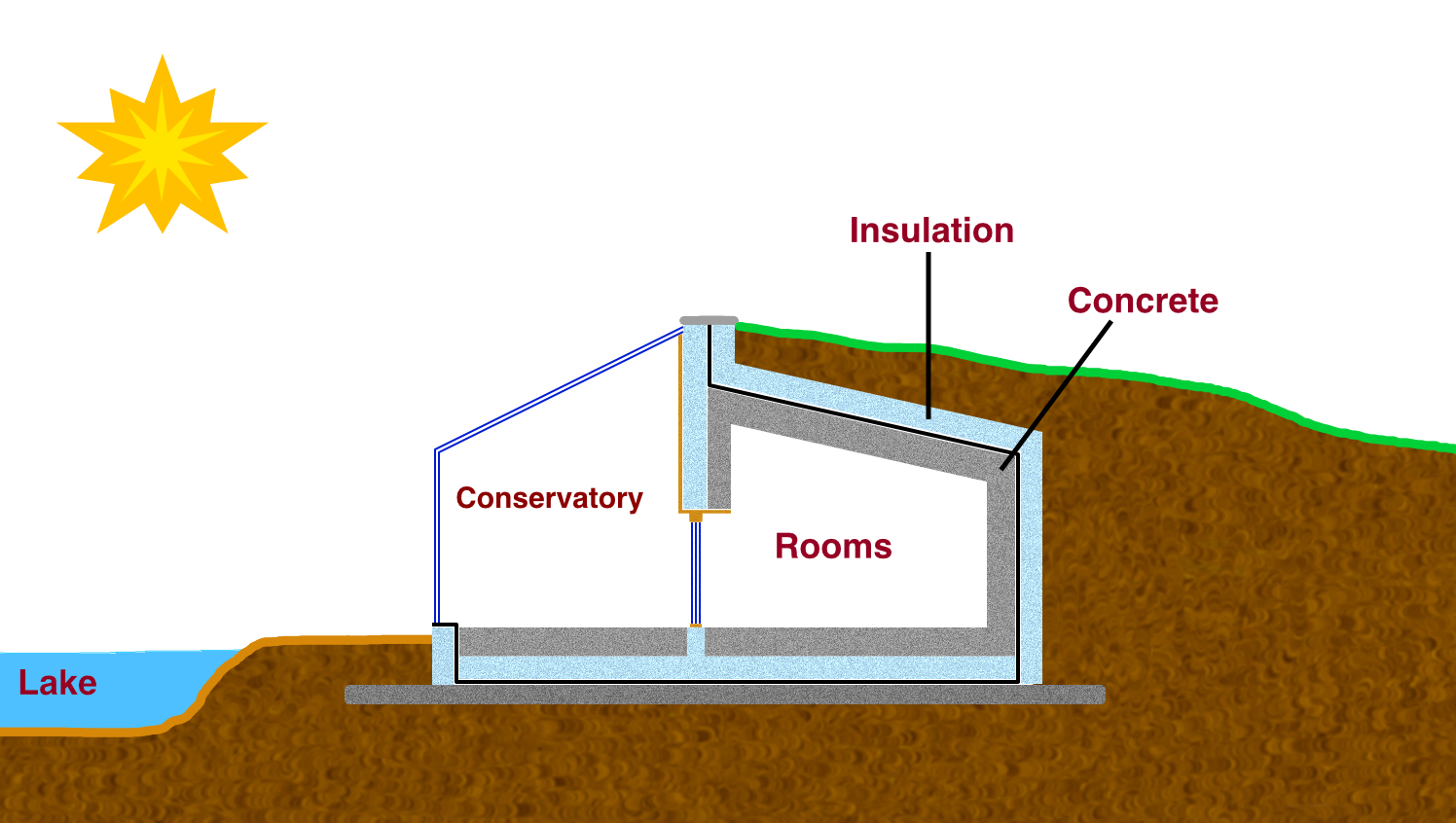

Nearby was a plague village; the site was chosen slightly away from this, to avoid disturbing archaeological remains. Meanwhile, the development had to be shielded from view of the main road. This was a major factor leading to the earth sheltered design.

Design Principles

The intention was a community that was sustainable in all senses of the word: environmentally, and without sacrifice to Western standards of living. Common to most ‘eco’ buildings is the idea that we need to use as little energy as possible; and the energy we do use needs to be sustainable. Hockerton responds to this with their ‘energy hierarchy’, explained below.

Meanwhile, the designers were acutely aware that living sustainably must be accessible to all, even those on a low income. More radical concerns are also represented: for example, if all people on the planet ate a Western diet, there would not be enough land to produce that food.

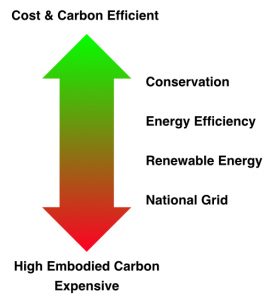

The Energy Hierarchy

Energy use at Hockerton is designed to minimise carbon emissions. However, cost is a key consideration: it drives peoples’ behaviour, though choice or necessity.

The ‘energy hierarchy’ is a way of thinking about energy strategies, factoring in both carbon emissions and cost. For both cost and carbon emissions, energy conservation is best, and national grid the worst.

However, the cheapest and lowest carbon strategies can come at the cost of increased complication and expense at the initial build stage. Hockerton, for example, invested in wind turbines and photovoltaic cells, and careful design for energy efficiency. Another ‘cost’ is educating people and changing their habits.

Design and Construction

The 5 original houses, designed by Prof. Brenda and Dr. Robert Vale, are built in one long row. They are earth-sheltered at the back, and greenhouses span the entire South frontage.

The earth-sheltered living space is 1 room deep, including a living room, kitchen/diner and 3 bedrooms. A large porch contains the ventilation and heat recovery (MVHR) unit and serves as an air lock to the main house. Triple-glazed double doors separate the rooms from the large conservatory area. The conservatory provides extra living space through much of the year, and pre-heats the air drawn in to the heat exchanger.

In front of the houses is a clay-lined lake, with a reed bed at one end, used to purify liquid waste. The lake water is clean enough to swim in, and contains carp that can be eaten – although I understand they have not been popular! Trout were considered, but would not have done well in still lake water.

Lake water is pumped to a 150m3 reservoir at the top of the site, holding enough for 75 days of washing for 20 inhabitants – an allowance of 80-100 litres per day per person. Water is used sparingly, for example with low flush toilets, and has never run out in practice. Drinking water is collected separately from the conservatory roof, stored in underground tanks, and filtered on demand.

Life at Hockerton

Residents commit one day of work a week to the site, being on a rota for tasks such as looking after sections of the vegetable patch, digging out the septic tank (apparently not as bad as it sounds…) or looking after the farm animals. Otherwise, they are free to get on with their normal lives – some are retired, and others have full time jobs, such as the University lecturer who showed me around.

Technical Performance

The main living space is well insulated and has an air tightness of 0.25 air changes per hour, and each unit has its own MVHR. The conservatories enable passive solar heating, and the terracotta tiled floors over thick concrete give significant thermal mass. Overheating is minimised by occupant behaviour: in hot weather, they can draw blinds in the conservatory, and open air vents.

In a standard house, space heating uses 60% of energy, with a rough average energy use of 7000 kwh/year. At Hockerton, there is no heating system. 50% of their heating is from the sun, 25% emitted from the inhabitants, and 25% from domestic machinery and lighting. Energy use in the houses averages 4380 kwh/year. With photovoltaic cells and wind turbines, Hockerton was in the past generating 100% of its electricity requirements, but since adopting electric vehicles they have not been able to achieve this.

The earth sheltered roof was not part of the energy strategy, as earth doesn’t have great insulating properties. However, it is efficient use of land: the space is used for growing vegetables, and keeping a large flock of chickens.

Further development and education

Further houses have been built on the site, no longer earth sheltered. There is also an education centre, and Hockerton hosts 6 site tours a year, as well as one off events. I attended a seminar about Biogas, led by the EU funded ISABEL project, which is conducting a consultation to explore introducing Biogas to the community.

Conclusion

Hockerton Housing Project demonstrates that ‘eco villages’ need not be places of subsistence living. Residents are able to live in a low impact way, with a perhaps surprisingly small time commitment to the community. A settlement like this needs cooperation and responsibility: a challenge but also a shining example.

See www.hockertonhousingproject.org.uk/visit/sustainable-living-tours for information on upcoming tours.

Note from Hockerton: there are 6 site tours a year, but also numerous other educational visits from schools and universities etc